Coins

|

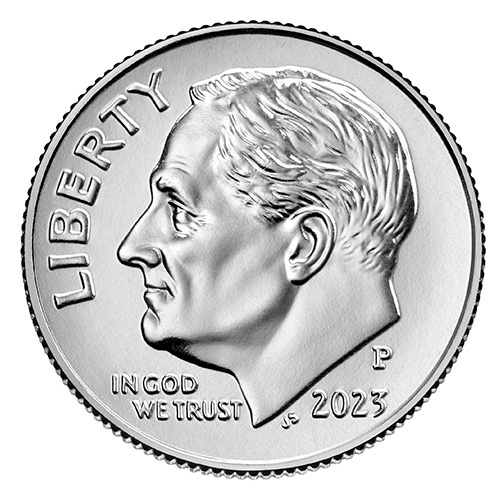

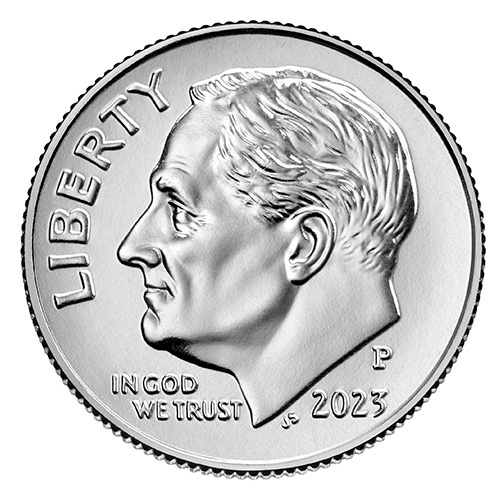

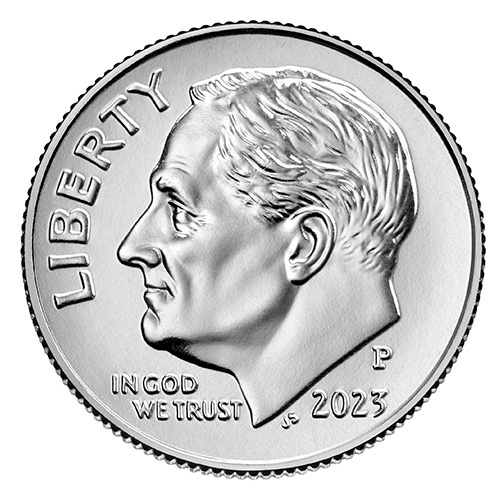

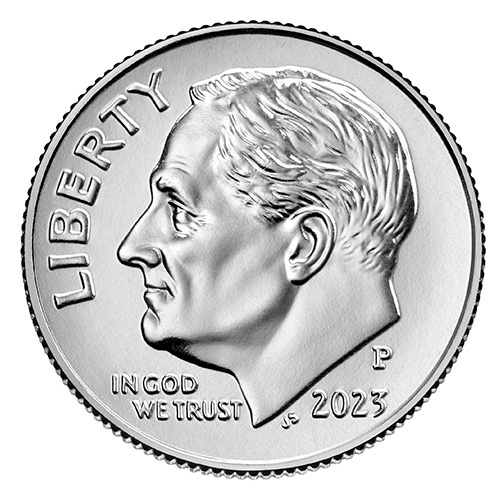

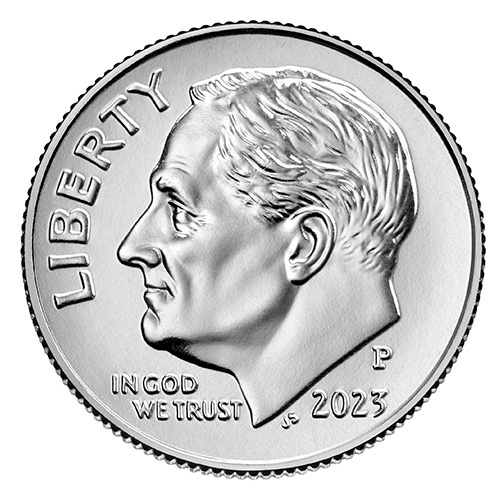

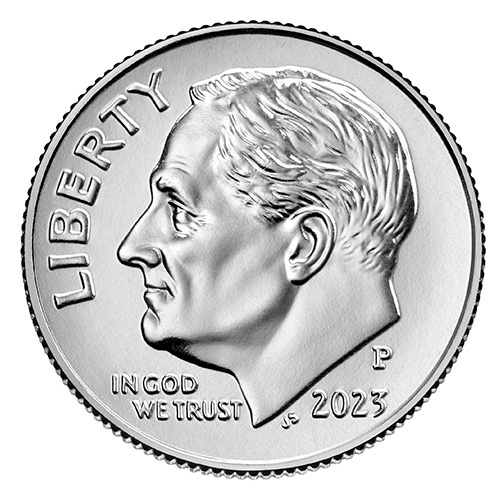

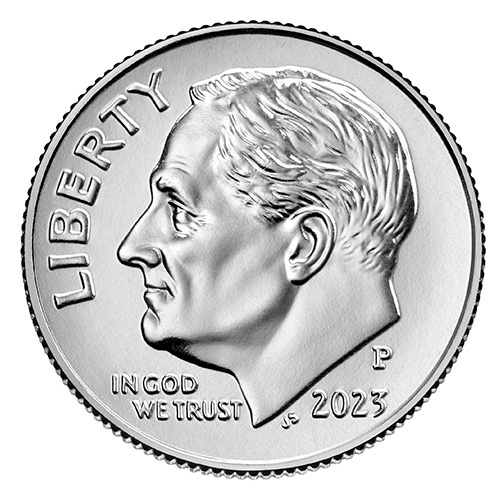

The dime, though small in size, is one of the most widely produced coins in the United States. Its creation is a carefully orchestrated process carried out by the U.S. Mint, which operates facilities in Philadelphia, Denver, San Francisco, and West Point. Each year, billions of dimes are struck to meet the demands of circulation, ensuring that this ten‑cent coin remains a constant presence in everyday transactions. The production of a dime begins with its metal composition. Since 1965, dimes have been made of a copper core clad in nickel, giving them their silver‑colored appearance. Large sheets of this copper‑nickel alloy are rolled out and fed into blanking machines, which punch out small discs called planchets. These planchets are the raw form of the coin, smooth and undecorated, but already sized to the dime’s exact dimensions. Next, the planchets undergo annealing, a heating process that softens the metal and prepares it for striking. They are then cleaned and polished to remove any residue, ensuring a smooth surface for the designs to be impressed. After this, the planchets are sent through an upsetting mill, which raises a slight rim around the edge. This rim not only protects the coin’s design from wear but also helps stack and align coins more easily. The most dramatic stage is the striking process. High‑pressure coin presses stamp the dime with its familiar designs: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s profile on the obverse and the torch, olive branch, and oak branch on the reverse. Each press can strike hundreds of coins per minute, with precision that ensures every detail is sharp and consistent. The ridged edge, known as reeding, is also formed during this stage, giving the dime its distinctive feel and preventing counterfeiting or shaving of metal. Once struck, the coins are subjected to inspection and quality control. Any dimes with flaws—such as weak strikes, off‑center images, or blemishes—are removed from circulation. The approved coins are then counted, bagged, and shipped to Federal Reserve banks, from where they enter circulation across the country. The scale of dime production is immense. In some years, the Mint has produced over two billion dimes, reflecting the coin’s importance in commerce. Despite its small size, the dime’s production requires advanced machinery, precise engineering, and careful oversight to maintain consistency across billions of coins. |

|---|